Genetic Lymphodepletion

Knockouts: Rag2 and Rag2/IL2rg

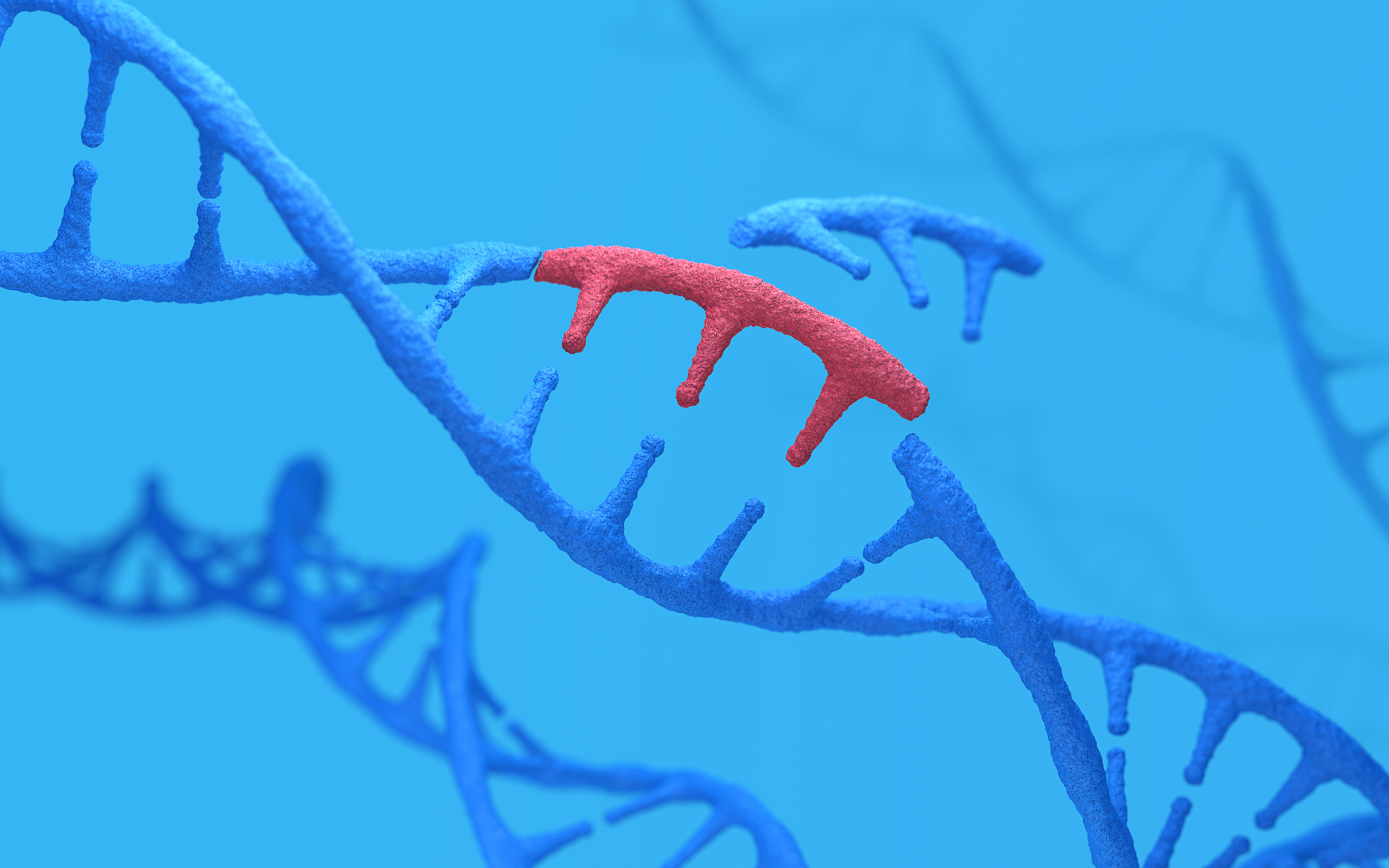

Rag2-deficient mice contain a mutation in the Rag2 gene that inactivates the production of the Rag2 protein – a key enzyme involved in V(D)J recombination. Because of the disruption in this process, mature B and T cells cannot form in these mice. Rag2-deficient animals are available on both the B6 and BALB/c backgrounds, making these mice versatile tools for a variety of immunologic studies.

Rag2 knockout (BALB/c) mice were used in a recent study to understand the immunosuppressive role of iNKT cells in arthritis, which is a disease driven by CD4+ T cells10. The Rag2 knockout background allowed for the adoptive transfer of autoreactive T cells in this model. Using a model of psoriatic arthritis induced by mannan injection, autoreactive CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into the Rag2 knockout mice with or without co-injection of iNKT cells. This tightly controlled system was used to demonstrate the specific immunosuppressive effect of iNKT cells on these autoreactive CD4+ T cells, providing more specific data than performing this study in an animal with a fully competent immune system.

Several studies have also used Rag2-deficient mice to study the influence of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) versus lymphoid cells in gut barrier damage11,12. Rag2 deficiency stalls the development of T and B cells, but not ILCs. One study looked at specific bacterial populations in the gut microbiome that protect against barrier damage, and which immune cells are required for this protection. The E. coli isolate GDAR2-2 drives ILC3 expansion in the gut and protects against C. rodentium infection and colitis in Rag2-deficient (B6) animals, suggesting that this protection is driven by ILC3s.12 In another study, to test the hypothesis that IL-33 drives ILC-mediated protection against amebic colitis, Rag2 knockout (B6) mice were treated with recombinant hIL-33 followed by amebic challenge, and mice were still protected from colitis. When the Rag2/IL2rg double KO model, which is deficient T cells, B cells, NK cells, and ILCs, was used, protection was lost.11

Indeed, Taconic’s Rag2/IL2rg double knockout model is useful for elucidating not just the influence of ILCs, but also of NK cells, when compared to the Rag2 knockout. One study used the biologic differences between these two strains to show that host NK cells were required to completely protect MB49 bladder carcinoma-bearing mice from death in conjunction with adoptive cell transfer13.

Of note, many older studies use the scid mouse, which is also deficient in T and B cells. However, compared to the Rag2-deficient models, the scid mutation is “leaky,” meaning that some functional T and B cells will in fact develop in mice bearing this mutation. Another key limitation of the scid models is their radio- and chemo-sensitivity due to the role of Prkdc in DNA damage repair.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)