The ability to directly and precisely modify the genome of mouse and rat embryos using CRISPR/Cas9 technology has revolutionized rodent model generation. The first CRISPR-modified mice were created in 2013. While this technology has simplified the process of creating genetically engineered mouse and rat models, there remains several important details to consider to maximize the successful creation of a model that meets project goals. Taconic Biosciences has generated CRISPR-modified mice and rats for years and has produced hundreds of different models. Our experience and expertise ensure that your project will meet your success criteria.

The CRISPR/Cas9 Technology

CRISPR/Cas9 technology is rapidly evolving. Taconic uses the latest CRISPR/Cas9 genome modification methodologies to generate genetically engineered mice and rat models. For example, Taconic was the first commercial provider to license Easi-CRISPR technology from the University of Nebraska. Taconic also holds CRISPR licenses from both ERS Genomics and the Broad Institute. See CRISPR/Cas9 Patent List.

Three key advantages of using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology:

- Reduced timelines compared to ES cell-based gene targeting methods

- Reduced cost compared to traditional methods

- Ability to modify a broad range of genetic backgrounds including existing genetically engineered models and models on complex genetic backgrounds

The CRISPR/Cas9 system uses a small RNA molecule called a guide RNA (gRNA) that complexes with Cas9 nuclease and guides it to a specific target site in the genome using sequence homology where the Cas9 protein induces a double-stranded DNA break (DSB). The DSB can be repaired by either of two major DNA repair pathways: Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). NHEJ is an error-prone process that often leads to mutations including small insertions or deletions (indels). HDR is a high-fidelity repair process that occurs less frequently than NHEJ and relies on the presence of a homologous DNA repair template. This process can be exploited to insert DNA segments with targeted alterations to create knock-in alleles.

The potential outcome of these repair events is illustrated in the diagram on the right leading to generation of a knockout and knock-in allele, respectively.

Easi-CRISPR

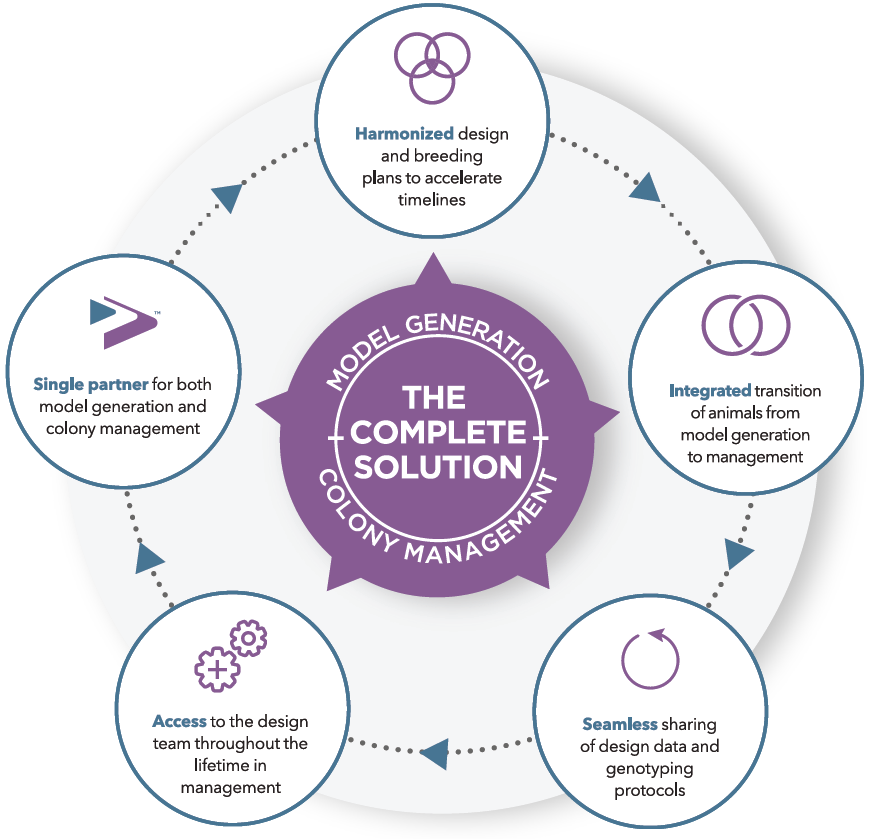

Overview of the Taconic CRISPR-Mediated Model Generation Workflow:

|

Large Knock‑Ins via CRISPR

Taconic’s toolbox includes access to powerful large knock‑in model generation using multiple CRISPR techniques, including Easi‑CRISPR and two-cell injection, to facilitate insertion of large segments of exogenous DNA into the genome with with high precision.

- Easi‑CRISPR leverages long single‑stranded DNA as repair templates in zygotes, enabling efficient integration of large cassettes like reporter genes, tags, or recombinases—all in a streamlined workflow.

- Two-cell injection takes advantage of a longer cell cycle and prolonged window for homology-directed repair, enhancing knock‑in efficiency and fidelity for complex edits.

Together, these methods allow the creation of large knock‑in alleles – such as fluorescent reporters, Cre drivers, epitope‑tagged proteins, and humanizations – without relying on traditional embryonic stem cell approaches. These models support your research across development, disease, and translational studies.

- Epitope Tag Knock-Ins

- Recombinase Knock-Ins

- Reporter Gene Knock-Ins

- Mini-Gene Knock-Ins

Epitope Tag Knock-Ins

Proteins can be tagged with short amino acid sequences to facilitate antibody-dependent assays (e.g., Western blot, ELISA, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, FACS, etc.). The sequence coding for the tag (e.g., HA, Flag™, V5, etc.), is inserted in a specific location within the gene, thus adding the desired amino acids to the endogenous protein sequence. The tag sequence can be inserted either at the 5' or the 3' end of the gene (one example shown below).

Recombinase Knock-ins

The expression of site-specific recombinases is used to delete a genomic region flanked by specific recognition sites (e.g., loxP sites for Cre recombinase and FRT for Flp recombinase). The sequence coding for the recombinase is inserted into a specific genomic locus to achieve tissue-specific expression (one example with Cre recombinase inserted at the 3' end is shown below).

In this example, a self-cleaving 2A peptide coding sequence is inserted between the EGFP sequence and the target gene sequence. However, Taconic employs multiple strategies to generate reported gene knock-in models.

Reporter Gene Knock-Ins

Reporter genes are used to identify cells expressing specific genes. The coding sequence for a wide variety of reporter proteins (e.g., EGFP, Luciferase, LacZ, etc.) is inserted in a specific genomic locus to achieve tissue-specific expression (one example with EGFP inserted at the 3' end is shown below).

Mini-Gene Knock-Ins

Mini-gene knock-ins enable the insertion of human coding sequences into the endogenous mouse locus (when an ortholog is present) to study human protein function in a native regulatory context. A human sequence – coding or cDNA, potentially including one or more introns as well – is inserted into the mouse gene immediately downstream of the translational start site. This allows researchers to investigate the functional impact of specific human gene variants or domains while maintaining physiologically relevant expression patterns. Mini-gene knock-ins are commonly used in areas such as neurology, oncology, and pharmacogenomics to enhance translatability in preclinical studies.

Featured Resources

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)