"It's just breeding... right?" You may want to carry out large cohort studies within the next 4-6 months, or to quickly recover a cryopreserved line from your collaborator to cross with your own knockout line. How difficult can it be?

"It's just breeding... right?" You may want to carry out large cohort studies within the next 4-6 months, or to quickly recover a cryopreserved line from your collaborator to cross with your own knockout line. How difficult can it be? The temptation of getting there fast may make you plunge into a new project right away. But early missteps in colony management can surface months into a breeding project, draining resources and causing months of delay.

What can you do to avoid these pitfalls? As "common sense" as it may seem, the answer lies in project planning. Spending time to develop a well-conceived and coordinated breeding plan at the beginning of a project can make the difference between the success or failure of your research.

How Can a Breeding Plan Benefit Your Research?

Sound planning can help you breed study cohorts with the desirable age, sex and genotype within the projected time frame. As no two projects are alike, a breeding plan should be customized to the scope and complexity of your project and address any potential risks. Taking a structured and proactive approach in up front planning will help minimize or avoid negative outcomes during the execution stage.Another benefit of a breeding plan is that it helps you keep your research budget under control. Breeding genetically engineered mouse or rat models may not be as straightforward as you think. To estimate the financial costs of your project with a high degree of accuracy, a breeding plan must take into consideration:

- Project Goals

- Type of Breeding Scheme

- Mating Combinations

- Quality of Input Material

- Health Status Requirement

- Phenotype Variability

- Genetic Background

- Use of Reproductive Technology

- Space or Time Constraints

- In-house or Outsourced Breeding

- Caging and Husbandry Costs

- Cost of Genotyping

- Technician Labor Costs

By factoring in all the above in the cost estimate, a breeding plan not only provides guidance and direction on managing project costs throughout its lifecycle, but supports better prediction of your budget expenditure patterns.

Five Steps to an Effective Breeding Plan

1. Define Success Before You Start

In Lewis Carroll's "Alice in Wonderland", Alice comes upon the Cheshire Cat and the two have a brief conversation that nicely illustrates the importance of defining success:The Cheshire Cat responds, "That depends a good deal on where you want to get to."

Alice, "I don't much care where."

The Cheshire Cat responds, "Then it doesn't much matter which way you go."

Alice, "...so long as I get somewhere."

The Cheshire Cat, "Oh, you're sure to do that, if only you walk long enough."

When developing a breeding plan for your genetically engineered research models, you should first put a good deal of thoughts into the composition of the cohorts that you need in your experiments. This includes the number of animals of course, but also must include consideration of the animals' genotypes, sex, degree to which the animals are age-matched, health profile, and most appropriate experimental controls.

In addition, one must consider how many experiments will require study cohorts and the required frequency of experiments. The ultimate goal of any breeding plan is to position the breeding colony to meet the specific needs of an experimental program, both short and long-term.

If you define those goals from the beginning, they will lead you to "what success looks like".

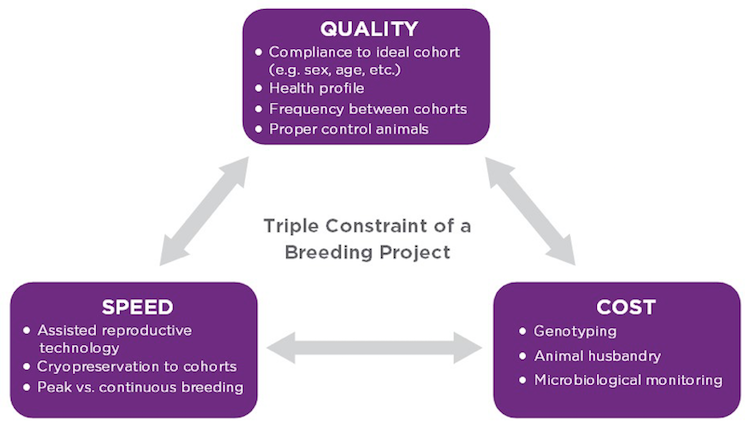

2. Strike a Balance Between Speed, Cost and Quality

All plans are bound to the "triple constraint" of speed, cost and quality. There is no avoiding it.In general, there are multiple ways to achieve the same goal. But which is the best for you? The answer often depends on which one of the three constraints is more critical than the other two. Over which constraint do you have the least room for compromise?

The best plan doesn't necessarily strike the "perfect" balance of the three elements, but one which prioritizes your most critical constraint while satisfying as best as possible the considerations of the other two.

The classic "pilot" experiment illustrates one such balance. A pilot experiment is most often done to generate just enough of the right research data to determine if further investment is warranted. Hence, a pilot experiment tends to biased toward lowering costs (investment), most often at the expense of speed and quality. In the end, it is not balanced but rather biased toward the constraint which you decide is most important.

3. Use Performance Metrics as Trail Markers

Once you are satisfied with your definition of success and balance of the triple constraint, it is time to determine how you will measure adherence to the plan once you start. Often, these performance metrics are obvious enough to "jump off the page".All project plans require you to make some assumptions as to how your starting materials will perform, and performance metrics are measurements, which inform you if your assumptions were accurate or not. In breeding of genetically engineered models, these assumptions tend to focus on fecundity (number of pregnancies, offspring per pregnancy, etc.), viability (number of animals that survive to study age), genetic allele segregation and sex ratios. One must make certain educated assumptions on these elements during the planning stage, but these must then be measured during execution to validate these assumptions as well as alert you if adjustments to the plan are necessary.

Defining performance metrics up front allows you to hone in on key milestones. Knowing when you expect to meet the next milestone and monitoring key check points along the way may show that all is on track. Alternatively, if monitoring reveals the project has been delayed due to unanticipated phenotypes, or poor breeding, you can better compensate downstream by adjusting the plan to meet the target or resetting and aligning expectations when appropriate.

Finally, monitoring progress allows one to determine what parts of the project were successful and parts that were less successful, lessons learned for more effective and precise planning for subsequent projects.

4. The Key is in the Contingencies

– Victor Hugo ( Les Misérables)

Your breeding plan is a road map, but almost all destinations can be reached by multiple routes from a single starting point. A good plan clearly highlights the ideal, or "critical path", to reach success. A great plan includes potential contingency paths if the desired path is not available or not working as planned.

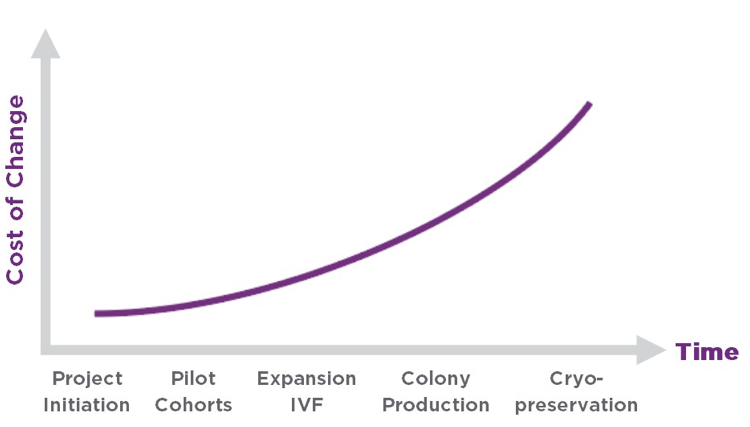

It is always best to develop contingency plans in advance. Having to stop to collect data, opinions, expertise and determine a new path once a plan is underway will cost time and resources (see Figure below).

Having contingency plans mapped out can reduce this risk considerably.

Having contingency plans mapped out can reduce this risk considerably. Equally important, and often forgotten, is the importance of determining the "triggers" in your performance metrics (see #3) that would alert you that it is time to veer from the critical path and onto a predefined contingency plan. Ultimately, planning for contingencies and performance-based triggers allows you to maintain your momentum from beginning to end despite the "unforeseen".

5. Get Your Colleagues and Stakeholders on Board

The final critical success factor for your breeding project is stakeholder expectations management.Rodent colony management typically requires the collaboration of a number of people across different functional areas, including researchers, program directors, procurement managers, veterinarians, lab managers and vivarium facility managers. A breeding plan can be used as a communication tool to ensure that all individuals involved in the project are aligned in regard to project scope, requirements, milestones, timeline and budget.

Regardless of your role in the organization, you can use the breeding plan to engage with the right stakeholders to gain their support for your project.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)